As you, coffee professionals, may have noticed, in recent years, coffee has gained truly remarkable momentum. 122 million bags in the international market, while the value of coffee grew by 90% in two years. Without distinguishing between consumer coffee and specialty coffee, it is undeniable that the growth in production and exportation from the main producing countries has been particularly massive.

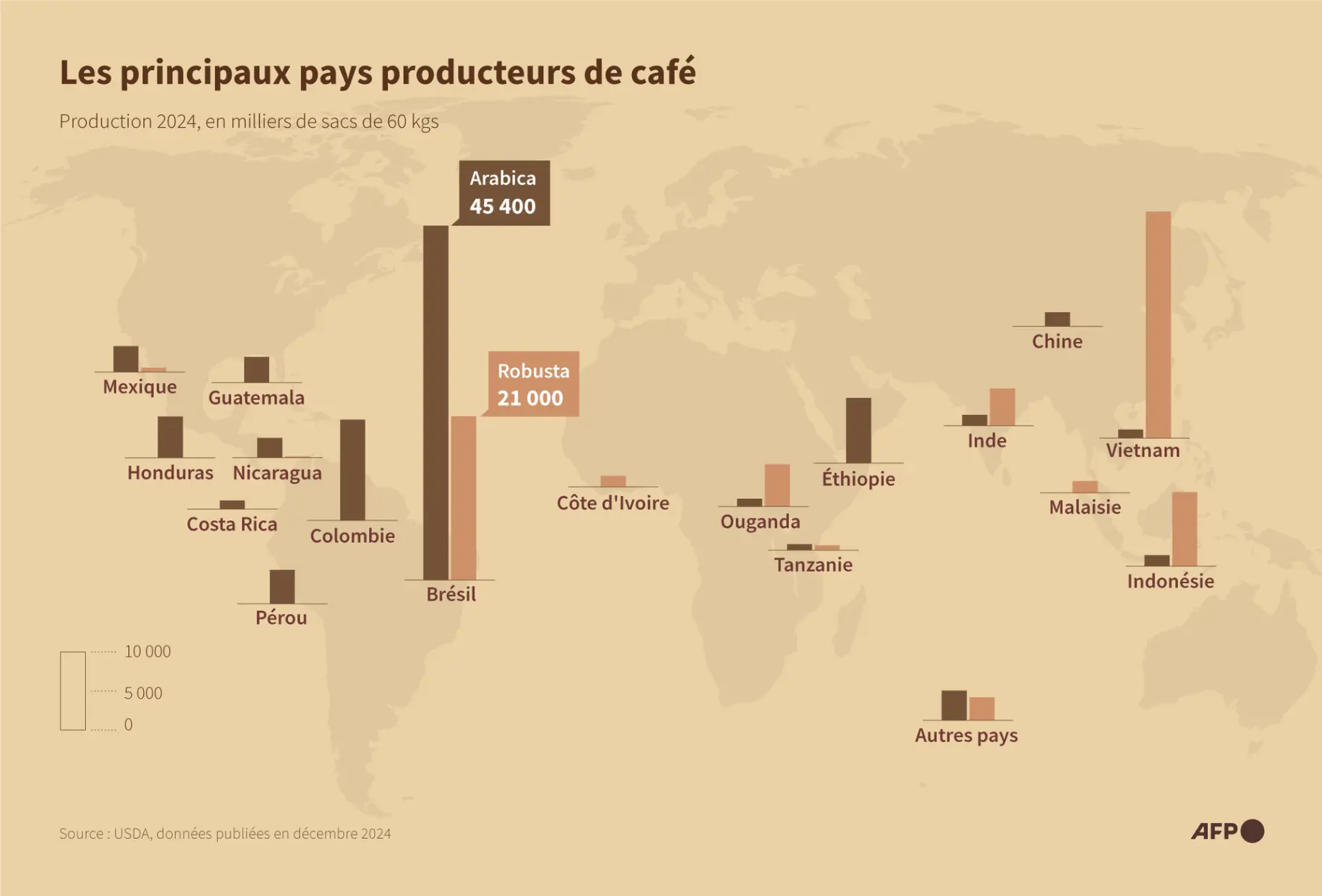

Among the historical producing countries are Indonesia, with 570,000 tons projected for 2024; Colombia, with 1,080,000 tons, breaking a 33-year record; Vietnam and Ethiopia have seen record productions and exports. New players such as Peru, Ecuador, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua are also emerging. These countries are progressively gaining more space alongside the historical leaders, with Brazil being responsible for the export of 3,840,000 tons, although these figures are declining, especially in the current context of international trade disrupted by U.S. politics.

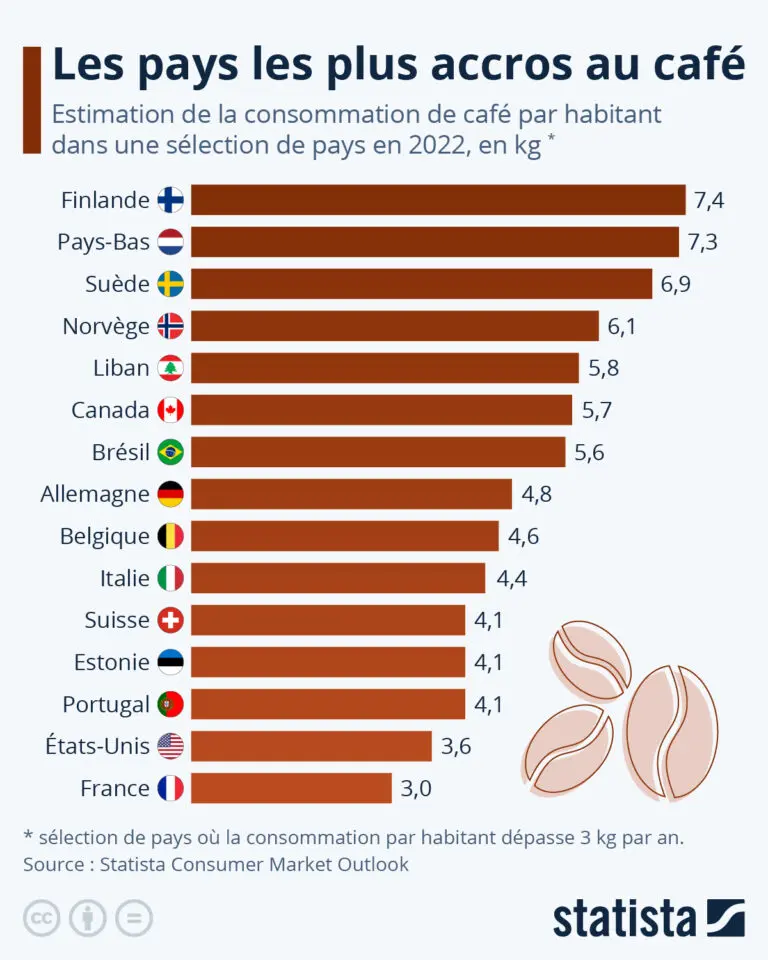

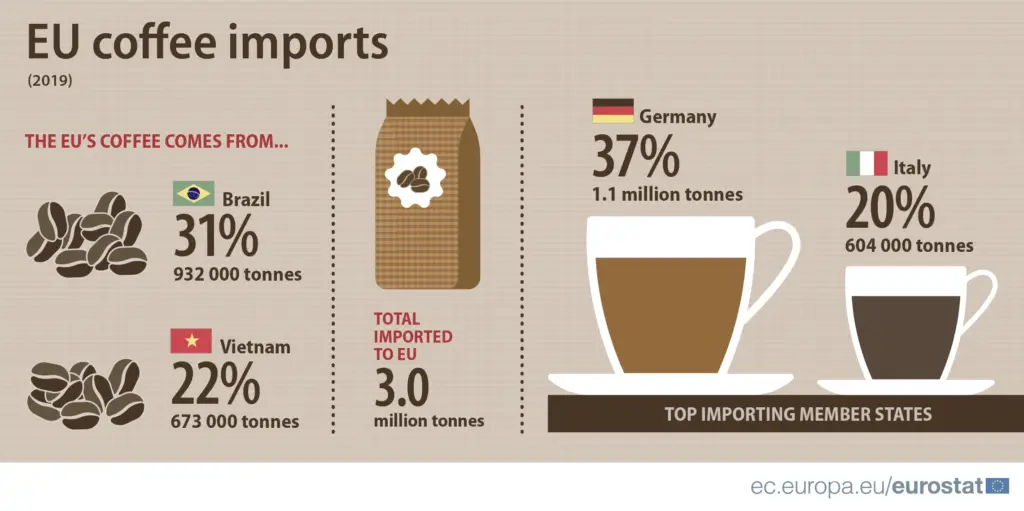

Coffee, along with cocoa, is the agricultural product that most transits through the international market: nearly three-quarters (70 to 75% depending on the year) of global production is destined for international trade. The main importers continue to be industrialized countries, both economically and culturally capable of investing in the importation of consumer coffee and specialty coffees. The United States, for example, consumes approximately 25 million 60 kg bags, which is 1,560,000 tons. Europe, especially the Benelux, exceeds 3,000,000 tons, closely followed by China and the Middle East. France is also beginning to follow this trend, especially in specialty coffee, with an average of 228,000 tons of green coffee imported annually between 2012 and 2021, of which 5 to 8% corresponds to specialty coffee.

The international coffee trade

Of the 14 million bags produced, 13 million are exported. Almost 69% of Colombian production is destined for European and American buyers, of which 40% goes to the United States and 19% to Europe. The United States remains a key player, but globally Europe continues to be the largest consumer of coffee. Demand continues to rise, while scarcity intensifies, driving the value of coffee in financial markets to over $4 per pound.

We talk about scarcity because coffee, with its production density, does not have as many hectares dedicated to its cultivation as other products, and there are deforestation regulations that limit the extent of production. Coffee globally has 11 million hectares dedicated to its production, a minority compared to cereals or soybeans.

In 2024, the global coffee market experienced record volatility of 10.5%, driven by extreme weather conditions and strong financial speculation. Droughts in Brazil and Vietnam reduced harvests, causing price increases of up to 90% for arabica. Exports were reorganized: robusta advanced, while other varieties declined, increasing uncertainty. Investors, sensitive to weather forecasts and supply tensions, amplified these price movements. In France, this increase translated into higher coffee prices for both consumers and businesses. This situation illustrates the fragility of a global industry exposed to both climate risks and speculative dynamics.

Risks and challenges for producers

This situation shows great potential, but also several risks, especially for specialty coffee and its producers. Although production and export are growing, one must ask whether producers can truly make a living from it, whether this growth includes quality coffees, or if it only favors industrial varieties and production methods, harming the environment and under the influence of stock market speculation. This reality limits the bargaining power of buyers, especially in the face of the multiple intermediaries in the supply chain. Coffee can become a victim of its own success, particularly specialty coffees, whose costs can reach levels too high to justify an investment in Europe, both for professional intermediaries, roasters, sellers, or consumers.

Some economic observers of the coffee industry, both in the industrial and specialty segments, point out that despite the intense volume of exports to Europe, the current logistical and customs model is not favorable for producers. They see their margins reduced by transportation costs and administrative and customs procedures, which are much heavier than in other emerging markets like China. At Finca, we have found that managing these processes individually is extremely complex. Experience shows that if quantities are consolidated or grouped, costs can be optimized and processes simplified. To export and import to Europe, it is necessary to have networks, tools, and protocols that optimize costs. The solution lies in mutualizing exports and imports.

It is observed that most producing farms, without distinguishing between industrial and specialty coffee, are small operations, often less than 5 hectares, and produce nearly 70% of the coffee exported.

Who hasn’t heard of a roaster or coffee shop that invested several thousand euros to directly import their coffee, found on the Internet, as if it were a miracle?

But the reality is that this person often takes several months, even more than a year, to complete the import. One must identify one, two, or three intermediaries, obtain the authorization numbers to export, pay for quality and safety control licenses, manage transportation and all administrative tasks, and remove the cargo from warehouses or airports. We can agree that this logistical stage can be extremely long and costly, especially if done alone, without advice or a global vision of the process.